Start building a culture of growth today.

Join the hundreds of organisations embedding mentoring and empowering their teams with the Art of Mentoring.

22 May, 2023 | 8 mins read

Need some stats on mentoring to build your business case?

Getting a mentoring program approved can take some persuasion, especially if the decision-makers have not had the experience of being in a well-designed program.

Here are some useful statistics to help you build your business plan and develop a strong case.

Incidence of mentoring

A 2009 article that claimed 70% of Fortune 500 companies had mentoring programs. The figure would be far higher in the 2020s. But not every organisation belongs to the Fortune 500. Big companies are more likely to have formal mentoring programs, according to Art of Mentoring research with HR.com in 2022. So, how widespread is mentoring across workplaces, small and large? We found:

Almost two-thirds (64%) of survey respondents said they had a mentoring program. Large organizations were more likely to have a program (69%) compared to small (51%) and mid-size (41%) companies. These 2022 findings represented a large increase from when a similar survey was run in 2017 on the same topic. At that time, only one-third of surveyed organizations had a mentoring program in place.

In addition, 20% said that they only offered informal programs, whereas 18% said they only offer formal ones. The rest (26%) said they offer a combination of formal and informal programs.

Another study by Olivet-Nazarene University found that 76% of people think mentors are important, however, only 37% of people currently have one. Industries where employees were most likely to have had a mentor were Science (66%), Government (59%), and Education (57%) and least likely were Finance (45%), Skilled Labor/ Trades (44%) and Healthcare (43%).

The Art of Mentoring research also found that almost half (47%) of survey participants had general mentoring programs, which were open to all employees. About two-fifths engage in mentoring for high potential individuals (40%) and peer mentoring (39%). Incidence of diversity mentor programs was 23%, group mentoring 18%, graduate mentor programs 17%, reciprocal mentoring 14% and reverse mentor programs 9%.

Mentoring Effectiveness

Some time ago, my esteemed colleague Professor David Clutterbuck, a leading researcher and writer on coaching and mentoring, told a group of our clients that “highly effective mentoring programs deliver substantial learning for over 95% of mentees and 80% of mentors”.

But is there real evidence to support this and other outcomes for mentees, mentors and their organisations, as a result of mentoring?

The answer is a qualified “yes”. One of the biggest problems with mentoring research is one of definition and research design. There are many definitions of mentoring and a great deal of confusion over where mentoring stops and starts and how it is similar to and different from coaching, counselling, training, managing and consulting.

A review of published studies easily reveals the many benefits of mentoring – but are they all measuring the same thing in the same way? Possibly not, exactly, but there is still much to be learned from these studies, which support, in general, our own research findings and the kinds of outcomes that our mentoring programs achieve.

Here is a collection of stats:

Mentee Outcomes

In a meta-analysis of 43 mentoring research studies, Allen et al (2004) found compensation and promotion to be higher in mentored individuals (than their unmentored peers); higher career satisfaction and greater belief that their career would advance; higher job satisfaction as well as greater intention to stay.

Looking at this and individual studies (Catalyst, 1996; Dreher & Ash, 1990; Fagenson, 1989; Johnson & Scandura, 1994; Lankau & Scandura, 2002; Jones 2012; Chun et al, 2012), reported outcomes for mentees include:

In an often cited long-term study, Sun Microsystems found 25% of participants in a mentoring program had a salary grade change and mentees were promoted 5 times more often than their unmentored peers.

Another study found 87% of mentors and mentees feel empowered by their mentoring relationships and have developed greater confidence

Individual benefits for mentors

Mentoring consultants often receive feedback that the mentors gained as much as the mentees in a program. Studies (Hunt and Michael, 1983; Kram, 1985; Jones 2012; Chun et al, 2012) have shown these benefits for mentors:

In the Sun study mentioned earlier, mentors were promoted 6 times more often (than non-mentors).

Benefits to the organisation

Research has reported benefits at the organisational level, including employee commitment, motivation and retention, higher morale, better work relationships and better leadership (Fagenson-Eland et al., 1997; Wilson and Elman, 1996).

In a study by Hegstad & Wentling (2004), the five most frequently cited impacts of the formal mentoring programs included:

In the aforementioned Sun study, retention rates amongst mentees (72%) and mentors (69%) was favourably compared to the general retention rate across the organisation of 49%. Sun claim to have made $6.7 million in savings in avoided turnover and replacement costs. They also estimate an ROI of more than 1000% on their investment in mentoring.

There is little published data on the impact of mentoring on productivity. Some time ago, one of our clients, TNT, asked mentees to estimate the productivity improvement they had achieved as a result of mentoring. 48% of survey respondents said they believed they had gained more than a 50% improvement in productivity.

Another organisational benefit that is often overlooked is the leadership capacity development of mentors who participate in a mentoring program that offers them both training to enhance their developmental conversation skills and an opportunity to practice those skills with someone who is not a direct report.

In spite of the difficulties in comparing results across different types of studies, the trend is clear – the studies conclude that mentoring does have significant benefits not just for the individuals being mentored but also for the individuals providing the mentorship, as well as their supporting organisations.

When one considers that mentoring can contribute to the engagement, motivation, morale, affective well-being, career mobility, and leadership capacity of both mentees and mentors, it is likely that the impacts are grossly underestimated.

Cross-Gender Mentoring

Cornell University’s School of Industrial and Labor Relations found that mentoring programs boosted minority representation at the management level by 9% to 24% (compared to -2% to 18% with other diversity initiatives). The same study found that mentoring programs also dramatically improved promotion and retention rates for minorities and women—15% to 38% as compared to non-mentored employees.

Gender

There are two schools of thought about mentoring for women. Research evidence supports the benefits of mentoring, yet some people argue that women do not need mentoring, they need sponsorship. The truth is they need both, according to these US stats:

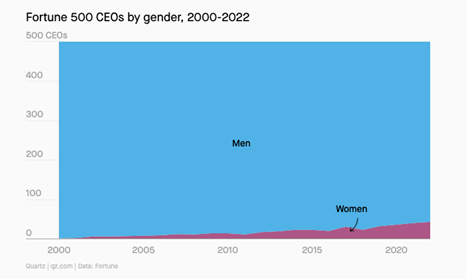

This graphic says all that needs to be said about how slow the progress is:

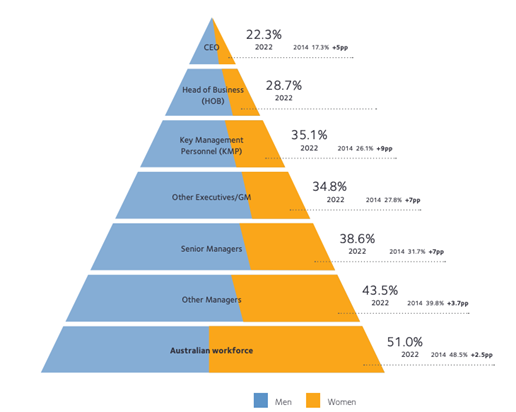

This is the situation in Australia:

The gender pay gap is still wide in many countries:

The Global Gender Gap Index has benchmarked the current state and evolution of gender parity across four key dimensions (Economic Participation and Opportunity, Educational Attainment, Health and Survival, and Political Empowerment) since 2006. In 2022, the global gender gap was closed by 68%. At the current rate of progress, it will still take 132 years to reach full parity.

Leading the field in closing the gender equity gap were Iceland (90%), Finland (86%) and Norway (85%).

The US was ranked 27th (77%) and Australia 43rd (74%) of 156 countries in 2022.

So, what about mentoring for women? Researchers suggest that women need mentoring for career support more than men do. Linehan and Walsh (1999) argued that mentoring is particularly important for women: “Mentoring relationships, whilst important for men, may be essential for women’s career development, as female managers face greater organisational, interpersonal and individual barriers to advancement” (p.348).

Indeed, there is evidence that mentoring actually benefits female mentees more than it does male mentees (Tharenou, 2005). It has also been suggested that e-mentoring is beneficial to mixed gender mentoring relationships, as the reduced level of social cues in electronic communication may enable a more power-free dialogue (Hamilton and Scandura, 2002).

In a review of Sheryl Sandberg’s book, Lean In, researchers provide evidence that mentoring focused on career achievement from role models that women can identify with is key to leadership success (Chrobot-Mason, Hoobler, Burno, 2019).

A study by Development Dimensions International (DDI) found that while nearly 80% of women in senior roles had served as formal mentors, only 63 % of women had ever had one. This is despite the fact that a majority of women view mentoring as valuable. Formal mentoring for women supports women who may not be confident to seek mentorship on their own.

In this study into a specific program for women in health and medical research, almost half of mentees cited that participation played a role in a promotion and also attributed program participation to other traditional metrics of academic research career success—including grants, awards and other leadership opportunities. Participants noted that essential for achieving those outcomes was an increase in confidence, as well as support from their mentors and network built through the program. Other benefits reported by mentees increased resilience and confidence.

While peer mentoring has already been found to have positives for students, a new study in Nature Communications looks at the longer-term impact of such schemes. It finds that the positive influence of peer monitoring for female students can last beyond the end of a degree.

©Melissa Richardson 2023

Read our case studies and learn how Art of Mentoring has helped organisations design and implement mentoring programs.

Download a Business Plan template.

REFERENCES

Allen, T. D., Eby, L. T., Poteet, M. L., Lentz, E., & Lima, L. (2004). Career benefits associated with mentoring for proteges: A meta-analytic review. Journal of Applied Psychology, 89, 127–136.

Catalyst. (1993). Mentoring: A guide to corporate programs and practices. New York: Author.

Chrobot-Mason, D., Hoobler, J., Burno, J. (2019). Lean In Versus The Literature: An Evidence-Based Examination. Academy of Management Perspectives, Vol. 33, No. 1, 110–130.

Chun, J K, Sosik, J J, Yun, N. (2012) A longitudinal study of mentor and protégé outcomes in formal mentoring relationships, Journal of Organizational Behavior, J. Organiz. Behav. 33, 1071–1094 (2012)

Dreher, G. P., & Ash, R. A. (1990). A comparative study of mentoring among men and women in managerial, professional, and technical positions. Journal of Applied Psychology, 75, 539-546.

Fagenson, E. A. (1989). The mentor advantage: Perceived career/job experiences of protégés versus non-protégés. Journal of Organizational Behavior, 10, 309–320.

Fagenson-Eland, E.A. , Marks, M.K. , & Amendola, K.L. (1997).Perceptions of mentoring relationships . Journal of Vocational Behavior, 51(1), 29-42

Hamilton, B and Scandura, T. (2002) “Implications for Organisational Learning and Development in a Wired World” In: Organisational Dynamics, volume 31, No 4, pp388-402, Elsevier Science, Inc.

Hegstad, C D & Wentling, R M. (2004) Human resource Development Quarterly, vol. 15, No. 4.

Hunt, D.M. , & Michael, C. (1983). Mentorship—A career training and development tool. Academy of Management Review, 8(3), 475-485

Johnson, N. B. and T. A. Scandura. 1994. ‘The effects of mentoring and sex-role style on male-female earnings’, Industrial Relations, 33, 263-274.

Jones, J. (2012) An Analysis of Learning Outcomes within Formal Mentoring Relationships, International Journal of Evidence Based Coaching and Mentoring Vol. 10, No. 1, Page 57

Kram, K.E. (1985). Mentoring at work: Developmental relationships in organizational life. Glenview, IL: Scott, Foresman .

Lankau, M J and Scandura, T A. (2002). An Investigation of Personal Learning in Mentoring Relationships: Content, Antecedents, and Consequences; The Academy of Management Journal, Vol. 45, No. pp. 779-790

Linehan, M. & Walsh, J.S. (1999) Mentoring Relationships and the Female Managerial Career, Career Development International, 4/7 pp348-352. MCB University Press.

Sun Microsystems Study (2009), downloaded from http://www.mentoringstandard.com/wp-content/uploads/2020/06/2009-Sun-Mentoring-1996-2000-Dickinson.p

Tharenou, P. (2005) Does Mentor Support Increase Women’s Career Advancement More than Men’s? The Differential Effects of Career and Psychosocial Support. Australian Journal of Management, Vol. 30, No. 1

Wilson, J. & Elman, N. (1990). Organizational benefits of mentoring. Academy of Management Executive, 4, 88-94 .

Download our introductory guide ‘The Ripple Effect’ to mentoring and learn the secrets to unleashing hidden value in your organisation

Compiled by our mentoring experts, this guide will introduce you to the secrets of unleashing hidden value in your organisation.

Art of Mentoring CRM needs the contact information you provide to us to contact you about our products and services. You may unsubscribe from these communications at any time. For information on how to unsubscribe, as well as our privacy practices and commitment to protecting your privacy, please review our Privacy Policy.

"*" indicates required fields

Join the hundreds of organisations embedding mentoring and empowering their teams with the Art of Mentoring.

By subscribing, you agree to Art of Mentoring contacting you about our products and services. You may unsubscribe from this communicaiton at any time using the ‘unsubscribe’ link at the bottom of our emails. The Privacy Policy, located on our website outlines our commitment to protecting your privacy.

"*" indicates required fields