Start building a culture of growth today.

Join the hundreds of organisations embedding mentoring and empowering their teams with the Art of Mentoring.

19 May, 2021 | 3 mins read

Time and time again, government agencies tell us that middle management and front-line management are the least engaged cohorts, based on their census or survey data. Like many organisations, government agencies often focus career development opportunities on new recruits, graduates, high potentials and on senior leaders. Layers in between, especially front-line staff who provide services to the public, have fewer development options made available to them.

With limited opportunities for promotion within the organisation and low visibility of the skills and experience needed to make an internal move, many look externally for a step-change in their career.

There are too many reasons why this problem needs to be solved to list them all, but here are a few:

Ehrich and Hansford (2008) reported that mentoring in government was usually targeted at graduates, new staff, trainees, current and aspiring leaders and specific groups who were the focus of diversity strategies. Today, we are seeing more government agencies who look to mentoring to empower their mid-career employees and retain them.

Mentoring is a cost-effective and proven way to:

When mentoring programs are run effectively, they achieve their objectives. Some government departments with whom we have worked have sought to build leadership capacity with mentoring, and discovered surprising extra benefits such as improved wellbeing, confidence and, in particular, attitude to employer and intention to stay.

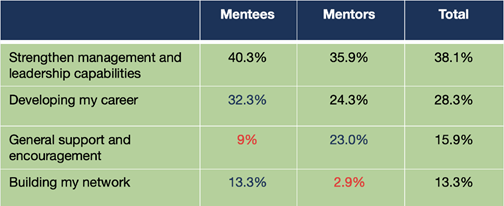

What are mentees after?

Recently Art of Mentoring analysed aggregate data from 13,000 participants across their programs – the benchmark report can be found here.

Mentees were asked to make a selection from four types of mentoring that they were seeking. Mentors were shown the same four and asked which they felt most equipped to offer. Across many different types of programs, professions and industries, mentees were very focused on career development and capability building.

Shouldn’t mentoring just be for people with potential?

It can be extraordinarily difficult to identify potential in any organisation. Professor David Clutterbuck argues that typical nine-box grid succession planning exercises simply don’t work – if they did, he says, then we wouldn’t have so many of the wrong people at the top. (Clutterbuck, 2012). Providing mentorship to people, who would otherwise be overlooked for development, allows them to self-identify as having potential, seek challenging assignments, build networks, develop skills and perhaps accelerate their careers, to the benefit of the public servant and the employing agency.

Public sector mentoring programs are more attractive than ever right now

In 2020 the pandemic impacted mentoring programs in one of two ways. Either programs were undersubscribed, because people were too busy or overwhelmed to make time for mentoring, or over-subscribed, because other professional development opportunities had dried up. We observed that public-sector programs tended to fall into the latter group. A state government program had to close applications after two weeks due to the deluge of mentee requests for mentoring.

There is an interesting gender difference too. In a recent government mentoring program open to any gender identity from any seniority level, 70% of the mentee applications were from women. This is consistent with a New Zealand study (Bhatta & Washington, 2003) that found that female public servants were more likely than their male counterparts to have a mentor. The researchers posit that women may have greater need for a mentor (to overcome systemic gender barriers to advancement) and/or women might make more deliberate efforts to seek support for career advancement. Either way, it is a trend we see across most public sector programs.

References:

Download our introductory guide ‘The Ripple Effect’ to mentoring and learn the secrets to unleashing hidden value in your organisation

Compiled by our mentoring experts, this guide will introduce you to the secrets of unleashing hidden value in your organisation.

Art of Mentoring CRM needs the contact information you provide to us to contact you about our products and services. You may unsubscribe from these communications at any time. For information on how to unsubscribe, as well as our privacy practices and commitment to protecting your privacy, please review our Privacy Policy.

"*" indicates required fields

Join the hundreds of organisations embedding mentoring and empowering their teams with the Art of Mentoring.

By subscribing, you agree to Art of Mentoring contacting you about our products and services. You may unsubscribe from this communicaiton at any time using the ‘unsubscribe’ link at the bottom of our emails. The Privacy Policy, located on our website outlines our commitment to protecting your privacy.

"*" indicates required fields